Martha

Kearsley is such a badass. She’s animated and articulate, a bookbinder who

makes playful and handsomely-crafted books, boxes, and stationery, as well as flower presses for drying flowers, Chump awards, and a huge variety of commissioned pieces. A long-time contractor at Harvard, Martha runs her own business—Strong Arm Bindery—from her studio in Portland, Maine, and also teaches at the North

Bennet Street School in Boston. I

caught up with her in her studio last month, and we talked about her latest

projects—which include camp logs whose plaid patterns are based on old

thermoses and “Dude Journals,” leather bound books

based on a form that dates back to the 3rd and 4th

century.

|

| Left image via Swallowfield |

How’d you

get into bookbinding?

And

I moved back to Boston, and it turns out the premier bookbinding program

happens to be there: North Bennet Street.

And then I got hired to do conservation work at Harvard. And I did that for a

long time, even when I moved here and started my own business, I was traveling

down to Boston, and still working with as many people as I could, because

that’s how you realize, ‘oh, I don’t have to always do this the same way…’

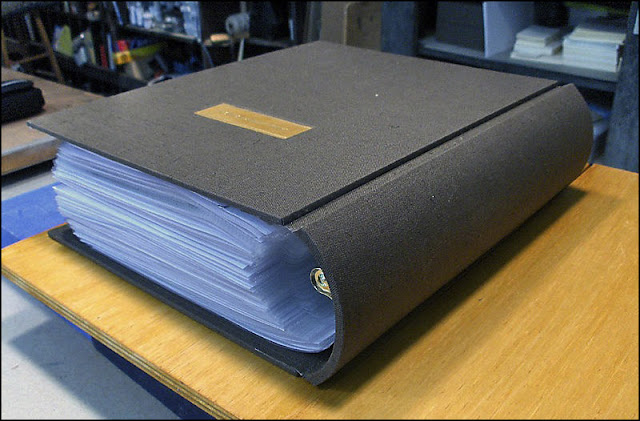

Well,

[the camp logs are one thing; they're based on old

thermoses from the 1950s]. And then this, this has nothing to do with

Camp Logs anymore, we’ve moved on to Dude Journals. This is one variation on a

leather travel journal, and this is from the 1700s, it belonged to this guy,

this dude, who was a boot-maker. It’s

is called an occasional diary, a cash account while he’s moving around, making

appointments…and it’s a form that I am crazy for… the way it wraps is a really

old form—the earliest examples we have are from the third and fourth century .

It’s a Coptic form—the copts were a Christian sect in North Africa, in Egypt,

and they were famous for their monasteries. They would have a text block of

papyrus and then wrap it with whatever leather they had around. Isn’t that

nuts? And it was the fourth century so there were no rules, they were just

like, ‘Well, we need something to protect it, so they just make this crazy

band…’ and it works! It just totally got me going, I was so excited about it.

Bible repair

work?

No.

That was what it was for two years… bibles, bibles, bibles. I have a couple of

bibles, but now… well, this woman had a water main break in her house, and a

whole bunch of her family archives were damaged…. I think I have about twenty

books that I’m working on from her family’s history.

How do

people find you?

That

time, they found me from a paper conservator in town. She brought her books to her, and she's like, 'oh, well, I’m not really into structure, but I know

somebody who can make the albums.' I’m working with her on a lot of it, which is

fun.

That

was in reference to when my brother was here, and [we had an intern], and we

were all working together. But, it kind of comes in waves. The most recent

collaboration was [a poster for a camping trip with a group of friends], and

that was me and a couple of friends who were just kind of goofing off.

Do you

collaborate with people across the nation? Or mostly with local people?

I

collaborated with a friend of mine who lives in Dublin, Ireland. We did that by

email and telephone. I had made him a notebook, just for a gift. And he filled

it with all these drawings, these speculative drawings for potential gallery

installations. And then he sent it back to me, and I scanned it, and printed it

out on the Epson. He and his wife were making decisions about the layout and

the cloth and the feel of the whole thing and I was just cranking it out. And

then he wound up using it—he’d send it to galleries and basically they would go

through it and say, have you done this one yet? And he’d be like no, and he’d

go and do it. It was very cool, some shrewd marketing on his part. So that was

probably my happiest collaboration… long distance.

It looks

gorgeous! What are some of the strangest projects you’ve worked on? I was

checking out your three-ring binder project…

The

Chop Shop one? Yeah, that was cool. Somebody brought in. It was this blown-out

three ring binder… they’d put too much stuff in it. So they wanted a bound book

with, you know, they still wanted it on three rings. So we just found this huge

piece of hardware that was three ringed, and used epoxy I think, and the back

of a big mailing tube to make the spine, and it worked.

I

did a box for a collection at Baker Library. Baker Library is the business

library at Harvard, and they have a really cool collection on this history of,

just, doing business, … they way that people make their way in the world. And

it goes over everything from, literally the banana republics down in South

America to the railroads across the country, to people back in the sixteenth

century who were apprentices to tailors, and their notebooks, and it’s some

really cool stuff. And those would just be patterns; tailor apprentice books

are almost like cartoons, they’re just drawings of a guy’s outfit, but without

the guy in it. Really simple, really straightforward.

Anyway,

I made a box for a collection of stuff that belonged to a guy who was involved

in the opium trade. He would go over and get opium and bring it back for people

who would make tinctures and tonics and whatever… and so, it was a box that

contained his glasses, pipe (for regular tobacco), his passport, his wallet…

and it was a series of drawers. I worked on it with my brother. You’d pull the

drawer out, and the object inside couldn’t move, so we had to make these drop

down pieces that were the exact dimensions of the object, so that the [objects]

could rest inside. That was fun.

Have boxes

and books always gone together historically?

I

think they’ve gone together. They’re based on the same measurements and the

same materials. They’re both about building houses for something.

Can you tell

me more about your Harvard projects?

I

was working out of the Weissman Preservation Center, a huge conservation lab.

The system at Harvard… it’s going through changes but up to a certain point,

every library has it’s own budget.

Like, the Baker Library has it’s own conservator, and the Fine Arts

Library has it's own conservator. I

was under contract as a book conservator to work on parts of just about every

collection. There would be a project that was small enough, and they’d hire me.

I’d work on, like, the maps library had a bunch of old atlases, so I worked on

that for half a year, or I worked for the archives department, which is Harvard’s

own archives, so there would be student notebooks from the 1700s, their notes

on divinity or on the business school classes. So that was on site, and at the

same time I was doing box-making here for the Fine Arts Library. They have

oversized print collections. It’s beautiful printing but it’s on crappy paper,

so there’s no way to bind it…the best way to do it is put the book into a box,

so that’s what I was doing for a long time, about four years.

Yeah,

that was really the fun part of it. You get to handle and treat really

amazingly weird stuff. And in my case, none of it’s linear, because it might be

a photo album of Central Park just after it was planted---that would be one

thing I was working on, and then the next week there’d be something else,

something from the 1700s, or something more modern. And, yeah, that was the

part I really liked about it; it teaches me history in this weird eclectic

way…. It’s better for my brain than doing it all in a line.

I

miss it, I miss the people, and I miss the camaraderie. But I still get

to see some interesting things coming across my desk. Harvard lost a third of

their endowment in 2008, so that was it. And they gave me fair warning, and

that’s when I started teaching.

How do you

like teaching?

I

love it. I absolutely love it.

|

| Image VIA |